An Incredible Account of 2009 Furnace Creek 508

- Categories: Road Biking

- Comments(14)

- Previous Post

- Next Post

When I cannot ride, I read about other people’s rides. I had heard of Furnace Creek 508 from our ultra distance cycling friend Mike. Following is a description of this race on their office website:

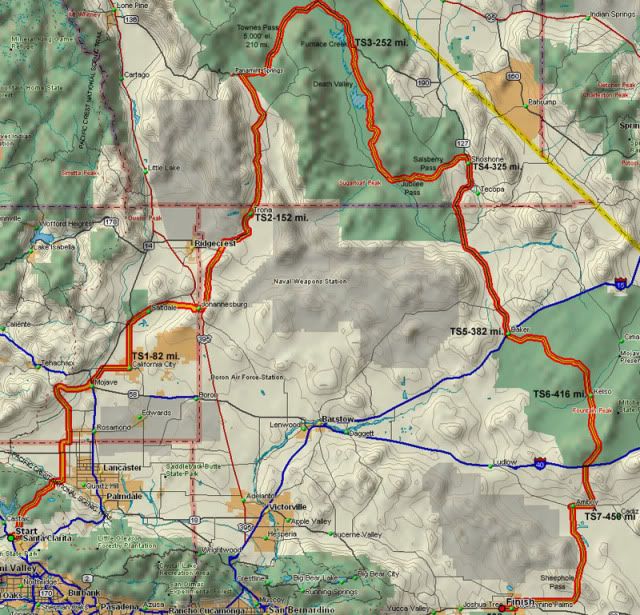

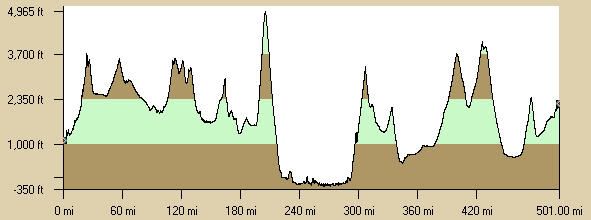

Founded by John Marino in 1983 and known as “The Toughest 48 hours in Sport,” it is the world’s premier ultramarathon bicycle race. This 508-mile bicycle race is revered the world over for its epic mountain climbs, stark desert scenery, desolate roads, and its reputation as one of the toughest but most gratifying endurance challenges available, bar none. The course has a total elevation gain of over 35,000′, crosses ten mountain passes, and stretches from Santa Clarita (just north of Los Angeles), across the Mojave Desert, through Death Valley, to Twentynine Palms. Solo, two-person relay, and four-person relay divisions are offered with a field limit of app. 200 racers.

I stumbled upon the 2009 Furnace Creek 508 thread on bikeforums.net. There were various accounts of the horrendous wind that the racers encountered. Anyone who comes to do a race like this, you know he/she has gone through the training from hell, and yet, obviously, the wind was worse than hell. I, sitting in my couch staring at the routes and profiles on my computer screen, know all too well that I have no business at all to even speculate what I would have done in that condition. It’s tempting because it doesn’t cost me anything, but if I tried, I feel that it would be an insult to the racers who actually were there to experience it.

One racer among them all wrote an incredible account of his journey. He goes by the username Biker395 on the forum. He posted to the thread throughout a span of a week or so exposing us to his FC journey stage by stage. In between his postings, I found myself checking the thread frequently hoping to see a new update from him. I like to write trip reports and ride reports from my adventures too as you might have noticed on this site. There seems to be one common trait I share with him: our reports tend to be lengthy. However, his reports are way funnier, more gripping, and more inspiring. If only I could write as well as he does…. Oh wait, actually, if only IÂ could ride as well as he does…

After reading the Epilogue, Erik said to me, “You should make a copy of all his pieces and put them together so they won’t be lost.” And when he said that, I was already working on it on my computer. With the author’s generous permission, I’m re-posting the entire report here to keep the wonderful stories centralized. I also included the links to his original posts in the forum thread.

- The Prelude (original post)

- Stage I – Canyon Country to California City (original posts 1 and 2)

- Stage II – California City to Trona (original posts 1 and 2)

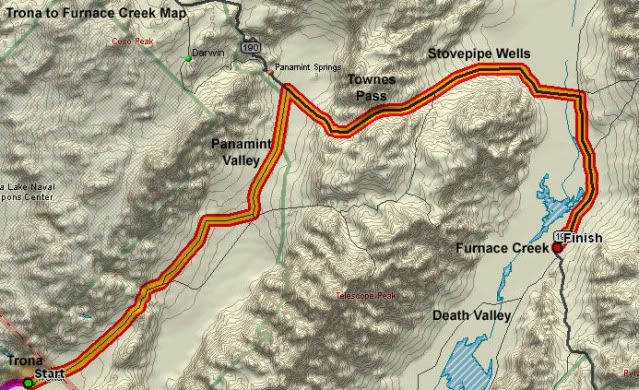

- Stage III – Trona to Furnace Creek (original posts 1 and 2)

- Stage IV – Furnace Creek to Shoshone (original posts 1 and 2)

- Stage V – Shoshone to Baker (original post)

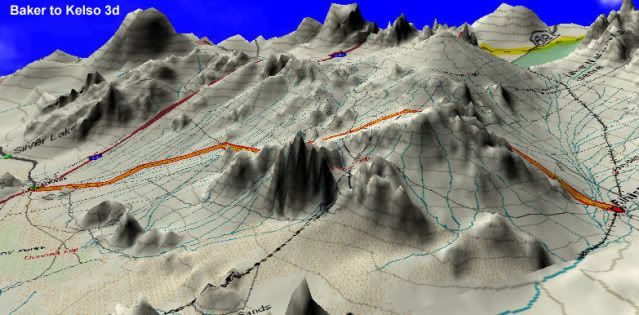

- Stage VI – Baker to Kelso (original post)

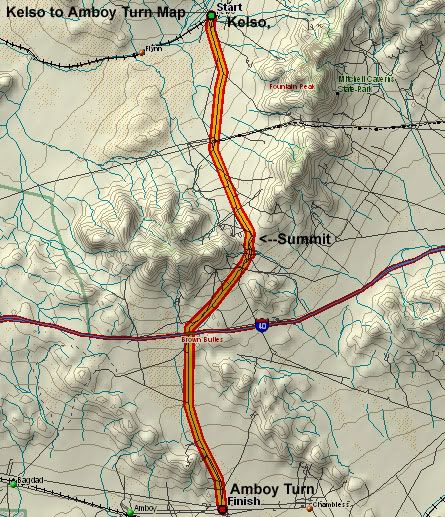

- Stage VII – Kelso to Almost Amboy (original post)

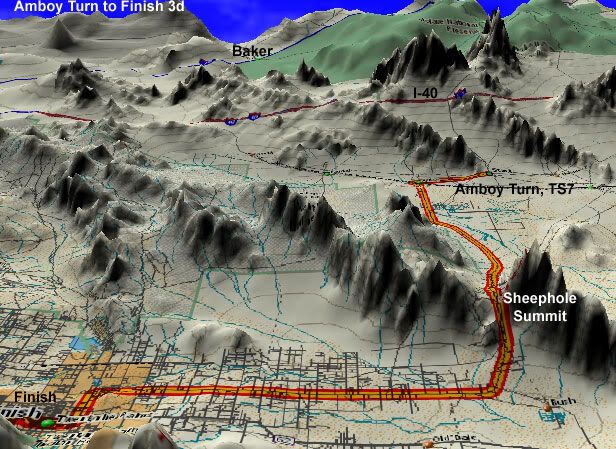

- Stage VIII – Almost Amboy to the Finish (original post)

- Epilogue (original post)

Now, brew yourself a pot of coffee, sit back in your comfy chair, and let the journey begin…

The Prelude

“Can I help you?”

“Yea, you can talk me outta this.” I muttered under my breath.

“Excuse me?”

“Uh, pancakes and hashbrowns, please.”

Bill and I are sitting down to breakfast at the Hilton Gardens Inn in Canyon Country. The time is 6AM. Within the hour, I would begin the 2009 Furnace Creek 508 … a 508 bicycle race through Death Valley. I had 48 hours to finish it.

“Coffee?”

I had been off of caffeine for the last two weeks, hoping to sensitize myself to it. Since I had planned to complete the ride with only an hour or two of sleep, I would defer the caffeine until later.

“No, thanks.”

Bill interjected. “Coffee makes a good laxative.”

Well, that is a horse of a different color. The last thing I wanted to so was to take an impromptu crap somewhere in the desert. That convinced me.

“On second throught, I’ll have some decaf.”

One year ago, I was at the same place, at the same time, waiting for the start of the 2008 Furnace Creek 508. I had planned to race that year, but fate had other plans. Just as I was beginning to get into the teeth of my training schedule, I had a serious crash. I broke 4 ribs, punctured a lung, broke my collarbone in two places, and got the mother of all road-rashes. The 508 was out.

And that wasn’t all. About a month after the crash, a “mass” was discovered in my head … somewhere between my teeth and my sinuses. Now, a “mass” could be anything from a benign cyst to … well …. anything. But I saw pictures of it, and it was ugly. Almost 3cm long and 2 cm wide. That doesn’t sound like much, but it’s huge when you are talking about something in your head.

Several doctors, two CT scans and an MRI later, and the nature of that “mass” had still been unresolved. Some opined that it was cancer. Some opined it was an ameloblastoma … a nasty invasive tumor that comes as close to cancer without actually being such. Both would require disfiguring surgery and require me to wear a prosthesis to cover my palate. Either might return. Either might kill me. It could be devastating. But there was an outside chance it was nothing.

And through a series of snafus, I still didn’t know what the “mass” actually was. There was a chance that it was merely a benign dentigerous cyst, but all of the doctors seemed to discount that possibility. Mad, late night searching on the Internet offered little hope that I could be that lucky. The mass was simply too big.

So on that day one year ago, I was a spectator … and a frightened, unwilling one at that. I was there because my friend Saralie was doing the ride. She was being crewed by friends Rick, Bill, and Mary. I was there to see them off on their grand adventure.

On that day, I had arrived early, and found myself sitting in that little breakfast area, watching the riders and their support crews anxiously chatting about the ride. For the first and only time in my 20+ years of cycling, I was on the outside looking in.

I didn’t belong. And I had no clue whether I would ever belong again.

And what do those people look like from the outside looking in? Healthy. Adventurous. People with a sparkle in their eye … who could look themselves in the mirror and not laugh at the suggestion that they could ride a bicycle 508 miles in 48 hours. People with incredibly devoted friends … willing to follow them for two days, sometimes at little better than walking speeds and dedicated to tend to their every need along the way, even if that meant slapping them upside the head and put them back on the bike.

A year ago, I knew all the participants were anxious about the ride, wondering if and when they would finish. I thought it to be sweet folly. The fact that they were there, ready to participate, with a serious chance of success … that was all that mattered.

When you are a participant, you don’t see things that way. You can’t. You have a myriad of things to fret over. But when you’re on the outside looking in, you see it for what it really is … an adventure where there really is no such thing as failure. All of the participants are winners, and all of them were to be admired. In fact, to be envied. My future uncertain, I doubted whether I would ever have the chance to join that group again.

As fate would have it, I got my chance. A biopsy finally determined that the “mass” was indeed a dentigerous cyst, and that disfiguring surgery would not be required. Oh, I needed surgery, and the recovery would be painful. Vicodin is wonderful stuff, but it can only do so much. But recover I did. And at the end, I managed to escape whole.

The crash injuries also healed as well, and as soon as I could, I registered for the 2009 Furnace Creek 508. A summer of training had passed. A summer that saw at least 10 double centuries. A triple century, followed by another 100 mile ride only hours later. Countless centuries with 10,000 feet of climbing. I saw the remains of a father and son hit by a drunk driver. I rode through fog, rain, and 110 degree heat. In short, I had trained as best I could.

I was eating breakfast. And I was no longer on the outside looking in. The day had come.

Sure, I was anxious. How anxious you ask? Well, anxious enough to have spent the last several hours … since 1:30 AM … tossing and turning in bed. Desperate to get some sleep, I sat as still as death, controlling my breathing and trying my best to relax and empty my head of any thoughts. It’s not easy concentrating on nothing.

I sleep best when it is cool, so I had turned the thermostat all the way down. Bill later likened the room to a meat locker.

Fitfully sleeping then waking up, I had plenty of opportunities to dream. In one of those dreams, my gloves were tattered and torn.

So yes, I was undeniably anxious.

The weather report did little to a$$uage my fears. About a week before the race, the weather models started to predict high winds over the race course.

Wind.

Neophyte cyclists fear many things. Heat. Cold. Rain. Hills. Traffic. Seat pain. Fatigue. But serious cyclists fear only one thing. Wind.

With electrolyte replacement and plenty of water, heat can be managed. You can always put on more clothes to deal with cold or rain. Seat pain and fatigue can be all but eliminated with the proper training.

And hills? Most serious cyclists will tell you that they enjoy hills. They offer a challenge while ascending and the reward of a screaming descent. Climbs can be long and steep, but eventually, they are vanquished. Cycling would indeed be boring without hills. I had grown to love climbing. No, hills are not a problem.

But wind … you don’t vanquish wind. It vanquishes you.

It gets in your eyes, your ears, and your mind. There is no summit. It pushes you back without mercy, and can do so for hundreds of miles. It can be in your face when your heading south, and stay in your face when you turn and head east. I dunno how that’s possible … it just is. Wind can turn a short 50 mile spin into an all-day sufferfest.

Wind is not to be fought. It is to be endured and outlasted. And more often than not, the wind wins … it outlasts you.

How bad were the predicted winds? Bad.

Well, in truth, not all bad. The winds were to start off slowly and from the West, presenting a cross wind as we rode through the Antelope Valley. Those same winds would be at our backs riding to California City from the windmills, and again while climbing to Randsburg.

As the day wore on, those winds were to turn to the South and to intensify to as much as 35 MPH. With any luck, those winds would blow us along though the Searles and Panamint Valleys. It was possible, even likely, that the winds would allow the racers to get to the base of the Townes Pass climb into Death Valley in record time.

The other side of Townes Pass would be another matter. There, the course turns South and into the wind. But by the time I got there, it would be evening, and the winds were predicted to die down. Nighttime winds in Death Valley were predicted to be southerly and perhaps 15 MPH.

Riding into the teeth of a 15 MPH wind is no fun, and having ridden through Death Valley before, I knew that the road condition was also far from ideal. So I fully expected Death Valley to be a long slog … probably the low point of the ride. How low? That depended on the wind.

So my fate was literally tied to a rapacious and fickle wind. I had good reason to be anxious.

But I was there. I was trained. I was on the inside looking out. With all my apprehension, I recognized that participation itself was a privilege and adventure reserved for the very few. That fact tempered any anxiousness I had about the outcome.

I was there … at least, I was there.

Bill and I arrived early the day before, and got the van checked in. A volunteer made sure that the van and my bicycle were properly equipped.

First the signs.

“CAUTION … BICYCLES AHEAD” on the rear. Check.

“THINK SKINK” on all 4 sides. Check

A red “slow vehicle” triangle on the rear. We had one that we hung on our rear wiper. Check.

Flashing yellow lights, that show only from the back. JC Whitney specials. Check.

Our turn signals, lights, and brake lights were all checked. And I discovered that one of my tail lights was out. While not a requirement, we were encouraged to get that replaced. That meant finding a place to buy a light, and more. It turns out that unlike any other car I’ve ever owned, the rear lights on my van are not easily accessible. OK … that would be another snafu to resolve.

“Let’s check your reflecive material on your bike.” Check. I had that in spades.

“And your headlight?”

“Mine’s on my helmet.”

“I dunno … I’m not sure if that is legal. I think it has to be on your handlebars.”

I brought out the rule book to show him that indeed, a light on the helmet was sufficient. But he checked with the race director anyway to confirm it. And confirm it, he did.

“I have a light … a very bright one.” I explained. “But I only intend to use it on the downhills. I don’t want it vibrating around on those crappy roads.”

He reluctantly agreed. And on our way to lunch (In N Out … Yum), Bill and I found a mechanic who had the tools to replace the brake light.

“Any more coffee? Excuse me … any more coffee?”

I was daydreaming. “Uh, no thanks.”

Other cyclists crazy enough to accept the challenge shuffled in. Most looked to be more than up to the task. Thin and muscular. Young. Confident. Many are sponsored, and outfitted in the regalia of their benefactors. I was none of those things. What the hell am I doing here again?

Bill and I arrived at breakfast early, and had no trouble finding a seat. But by now, the room was crowded with cyclists and their support crews, and many were looking for a place to sit. After finishing our breakfast with Rick and Saralie, we shoved off for our last minute preparations.

I joined them. We took a picture for posterity.

The first 25 miles of the 508 passes through the streets of Santa Clarita and then ascends San Francisquito Canyon, the scene of the greatest flood in California history. Since that road is narrow and has little shoulder, our support vans would not be following us in this section. Instead, they would wait for us at Johnson Summit, just past the little burg of Green Valley.

That meant that our support crews would leave the staging area before we did. It also meant that they would be unable to bid us farewell or take any pictures at the start of the ride.

It was cold. The low pressure system that was going to wreak havoc with the winds had also lowered the temperature substantially. The week before, it was well over 100 in the deserts. This weekend, it would get no warmer than 90 degrees, even in Death Valley. And right now, in Santa Clarita, it was about 50 degrees. It was a little chilly for wearing only shorts and armwarmers, but I knew we would warm up fast climbing out of Santa Clarita.

I wheeled over to the staging area.

The serious racers were already there, at the front of the pack. I took my position where I belonged … at the back.

I knew from previous experience that a lot of riders would charge out of the gate and attack the San Francisquito climb. With all my nervous energy, I knew I would be tempted to do the same. But this is a 500 mile race, and charging out of the gate is a fatal mistake for all but the strongest riders. This is definitely a tortise and hare event, and I had resolved a long time ago to be the tortise.

Being the tortise takes some mental discipline, something that does not come naturally to me. So I resolved to keep the rules simple. Start at the back, and do not stand up on the climb. Remain seated and spin.

I was waiting at the starting line for perhaps 5 or 10 minutes, but it seemed like an eternity. To pass the time, I chatted with the racer next to me. An ultramarathoner from British Columbia. We chatted about what kind of training we had done and whether we were prepared to go the distance. As an ultramarathoner, she had learned long ago what her body could take and how to pace herself. I had no doubt that she would finish.

The megaphoned race director had some words of wisdom for us before we left.

“Things happen out there that weren’t intended or expected. I encourage you to focus on getting to the finish line, no matter what.”

Boy, was that good advice.

We synchronized watches. Gawd, I hope finishing within 48 hours doesn’t come down to seconds.

A countdown. “5, 4, 3, 2, 1 … GO.”

And with the sirens of our police escort, we were off.

Stage I – Canyon Country to California City

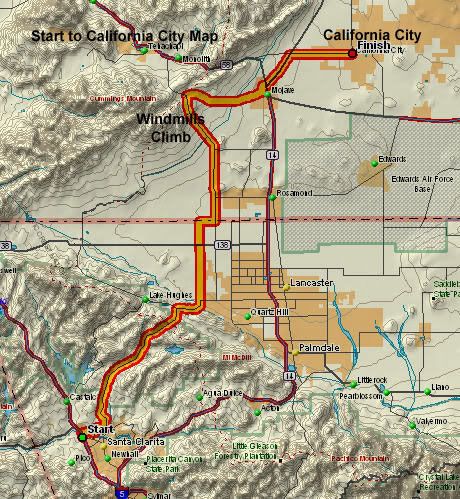

Here is the route for Stage I:

Here is the start line:

From the beginning, everything went according to plan … I was the last person to leave the staging area.

Immediately, the racers separated into a lead group and a following group, with a significant gap. Sheesh. We were warned that although we would have a police escort, if we fell too far behind the lead group, we may have to stop for a stoplight.

Pacing myself is one thing, but sitting out a series of stoplights while the rest of the pack moved on was too much, even for a tortoise. I decided to make up the gap and place myself at the back of the lead group. That was no challenge at all, but it was a challenge to do that while still keeping my heart rate down.

We got rockstar treatment in Santa Clarita. The police went off in front of us, closing streets so we didn’t have to stop. At this time of the morning, there weren’t many autos that had to wait for us. And, there wasn’t much of a wait, since we were a small group. But I couldn’t help wondering what those drivers would think if they knew how far we were all going.

“San Francisquito Canyon Roadâ€

We lose our police escort, and the ascent begins. I’ve ridden up this road only twice before. The first time, in a 20 MPH gusty head wind with blowing sand and dust. It was a grunt. The second time was on the 2006 Furnace Creek 508. I was surprised how quickly the climb went without the wind. I passed a lot of riders and surprised my crew when I appeared at the top so early.

But that time, I was riding in a two person relay team. This time, I was riding it all myself. It was tempting to stand up and fly right up the hill.

“Don’t.†I said to myself. “Easy.â€

With all the thinking and confabulating I did worrying about the winds, one thing I didn’t expect was a headwind going up this canyon. But there it was. It wasn’t strong, and it was cool. But it was there, and it was unexpected. Other than that, things were going well.

Now and again, a rider would stop to take a leak. Other than that, there wasn’t a lot of passing going on here. I didn’t pass many riders, nor did I get passed. The truly fast riders were long gone already.

It happened in an instant, and was over before I could do anything except scream.

“****!â€

A lone red crotch rocket screamed by me, going at least 60 MPH and missing me by perhaps 6 inches. He was going so fast, I saw him only for an instant in my rear view mirror before he passed, and only because I constantly check my mirror. I didn’t have a chance to react at all.

What’s the reason for the close call? There was no good reason. I was all the way on the right shoulder, about 3 inches to the right of the fog line. The road was clear … wide open. There was no reason for him to pass that close to me. No reason at all.

I have ridden well over 100,000 miles in my lifetime, and I can tell you that most motorists are quite courteous. They pass with plenty of room … at least the legally required three feet. I mean … after all, is there anything easier to pass than a bicycle?

Some are even downright friendly, giving you a thumbs up or other encouragement. You’d be surprised at how often that happens.

But then, there are the buttholes. They are on a machine that ways several times what you are, and they use that difference to bully you. Just like on a schoolyard. I don’t hate many things, but I do hate bullies.

I wonder if this guy realizes that there are reasons why the law requires safe passing distance. What need to swerve to avoid a rock? What if there is a wind gust? A flat tire? What if I sneeze? He hits me, and I’m seriously injured or killed. Why the hell would anyone want to do that? How would he feel, if driving my car, I passed him with a 50MPH differential, missing him by a mere 6 inches? I wonder if he realizes that doing what he did amounts to assault with a deadly weapon?

Usually, I blow that kind of idiocy off, but this one was very close and very stupid.

At once, my mind wavered from the 508 to the realm of noses and fists. I’m here to tell you that if I did happen to encounter this guy … let’s say at a 7-Eleven further up the road … I would have got off the bike and popped his stupid ass … no words, no statements, no questions. I wouldn’t give him any more warning or any more of a chance than he gave me. And it would be worth it.

Ooops. There’s my speed. I’m going too fast. I wonder why.

Still fuming, I arrived at the little town of Green Valley. A sweet little burg on San Francisquito Canyon Road, and a place where, for all the world, it looks like their biggest problem is keeping traffic to slow down to 30 MPH when passing through. No problem for me … I’m going uphill.

Some residents were there to greet us and cheer us on. Yay!

The summit isn’t far from here, and the road steepens as you approach it.

I began to pass a gent. I know that this is a race, but I like to chat with riders on the way up. What’s the alternative? Pregnant silence as I pass? Screw that.

We got to chatting about what was on my mind, of course (this is all about me, of course). The motorcyclist? Nope. The wind. I mentioned our prognosis. He responded.

“Well, nothing could be worse than 2004. I told myself that if I can make it through that, I can make it though anything.â€

“That bad?â€

“It was amazing. I barely finished. Ooops … I have to slow down … my heart rate is going too high.â€

I’ve never used a heart rate monitor. They’re good for making sure you pace yourself, but I’ve always just tried to listen to my body. I dunno. Maybe I should try one.

I was feeling OK with the speed we were going, so I went on, bidding him good luck. I would see him again.

Finally, the summit. On the other side was a short descent and a left turn. And there, my crew would be waiting for me. From this point on, I would have crew support. No more a$$holes on motorcycles.

There were marshals all over the course, making sure we came to a stop at each and every stop sign. Ordinarily, that is not a problem. But this last stop sign was at the top of a steep hill. I was able to downshift a few gears, but was still a grunt getting started. You can tell from the picture.

I passed my crew, waiting by the side of the road.

“HOW DO YOU FEEL?â€

From now on, any communication with my crew would be bursty yell sessions.

“FINE! I COULD USE SOME WATER!â€

The 508 has a great many rules. One of them is that until 6PM, my crew was obliged to follow me “leapfrog style.†That meant they would pass me, pull over onto the shoulder, and we would handoff food or water. My job was to toss them my water bottle, and theirs was to hand me a full one.

At the pre-ride meeting, they gave us some good advice about how to do this. Apparently, I forgot some of it. The first thing I forgot is that my crew would be looking to give me water before my water bottle was empty. No problem, I thought. I’ll just toss the half empty bottle to them.

Except one thing. A half empty bottle weighs a LOT more than an empty bottle. Here is the result.

Oops. From that point on, I was a little more careful about where I tossed the bottle.

The 508 is a race. So all the other riders and road crews are technically your competition. But invariably, as the race gets started, competition turns to comaraderie. Since support crews were leapfrogging the riders, that meant that I was repeatedly passed by support crews for other riders in the vicinity. And all of them clapped and yelled encouragement to each of us as we passed.

To be honest with you, this is the best part of the 508. The sweet comeraderie that can only be had in the company of others who enjoy suffering endured for no good reason.

Ah, the second climb of the ride. Into the windmills west of Mojave. This really isn’t a difficult climb … when the wind is not in your face. Trouble is, those windmills are there for good reason, and the wind usually IS at least partially in your face. This morning, the wind was coming almost directly from the west, and I was treated to a quartering headwind. And the wind was intensifying.

I wanted like anything to just stand up and climb this thing, but I stuck to my plan. I downshifted and spun.

I’ve done the 508 and other long races like this before. And in doing those rides, I’ve learned what my strengths and weaknesses are. One thing I have discovered is that I am a strong climber. Oh, there are many … very many who are better climbers than I. But among people who are about as fast as I on a long course, I typically pass people on the ascents, get passed on the descents, and almost hold my own on the flats. That pattern held true on this 508, even when I stuck to my plan to just spin up the hills.

So, on this second climb, I found myself leaving my leapfrogging partners behind. I finally reached the turn off back to Mojave and headed both downhill and with the wind.

Boy, did I fly. Before the ride, Bill had loaned me his wheels, and they included an 11-28 cassette. That 11 tooth top gear came in handy here, as it allowed me to keep pedaling when others could not. Downhill and with a strengthening wind at my back, I was flying along at over 30 MPH. Mojave came way too fast.

Mojave is a strange town, but I’ve always had a fondness for it. When you approach on Highway 14, all … and I mean ALL … of the businesses are on the east side of the road. There are railroad tracks just to the west of the highway, and nothing at all on the other side of those tracks. It’s as if no one dared build there for fear of being on “the other side of the tracks.â€

We would not enter Mojave itself … just skirt along the periphery of it.

Pity. I could use a SuperStar with cheese right about now.

I dunno what it was in this section, but somehow, all those delicious tailwinds turned into headwinds. I got on the aerobars and tried to hustle over to the California City turnoff, where I would again head East and with the wind.

In the 2006 508, I broke a cable somewhere along here, and lost a lot of time. The support van had headed off to wait for me at California City, and I was on my own. That meant I could only ride in my smallest chainring. Since I use a triple chainring (and have no shame in doing so), that meant that although I could have done 25 MPH easily though this section, I had to pedal furiously to make 18 MPH. I tried stopping to fix it by adjusting the stop on the front derailleur, but all I did was waste 5 minutes. It was frustrating to get passed like that because of a mechanical problem.

I had no such problems this year. By and by, I closed rapidly on another rider. I wondered aloud why they were going so slow, but the reason was apparent as I passed him. He was riding a fixie.

Fixies are bikes that have only one gear. You think it’s nuts to ride a bike 500 miles in 48 hours? Try doing it with only one gear. That means that you’ll be in too tall of a gear for almost any ascent. Nice, huh? And that’s not the half of it. There is no coasting on a fixie. So while us ordinary crazies are cruising downhill and with the wind at 30 MPH or more, these guys are trying to get down the hill, pushing *against* their pedals to slow down.

This year, there were two solos in the fixie category. One male, and one female. They were assured of a first place finish … if they finished. And as it turns out, that would be no easy feat.

Passing him seemed unfair … like I was cheating. But pass him I did.

His bike looked like a mirage. White, with beautiful pink spokes. I wondered aloud what that was all about.

I soon found out. His crew consisted of three attractive women, dressed in identical T-shirts. Each time they stopped to hand him water and what-not, they’d scramble about like good little crewmembers, but appeared to be having a grand old time doing it. They were a welcome relief from the drab desert landscape.

California City is even more interesting than Mojave. The city limits extend a crazy long distance into the sagebrush and creosote of the Mojave … including a portion of Highway 14 itself, 15 miles distant. It was promoted as a model development for retirees, with big plans for a lake and all kind of amenities. Along the way, something went wrong, and it never achieved it’s full promise. There are houses all right, but there are also a lot of empty,. weed infested streets. Still, I like it here.

At this point, I was hoping to beat my previous time into California City. Last time, I managed to get there in a little over 5 hours. Would I make it? Passing quickly though town, I made the obilgatory stop, a left turn, and I checked in with a time of just under 5 hours.

My plan was to eat and drink as much as possible *on the bike* and not in the rest stops. I knew that the weather or exhaustion may slow my pace dramatically, but I also knew that the key to finishing was to keep going and waste as little time in the time stations as possible.

My plan was also to change shorts about every 100 miles. We were not yet to 100 miles but since the next time station was a good number miles away in Trona, I decided to change there.

Kinda tough to have a semblance of modesty during endurance races. You have to change, and do it fast. I jumped into the front seat and without taking off my shoes, pulled the shorts off. Saralie had opened the side door and was looking for one thing or another.

“Don’t worry. I’m not looking.â€

“That’s OK … there’s nothing to see, anyway.â€

I think she was still sore about hitting her in the face with my water bottle:

“Yea, that’s about what I would have expected.â€

Stage II – California City to Trona

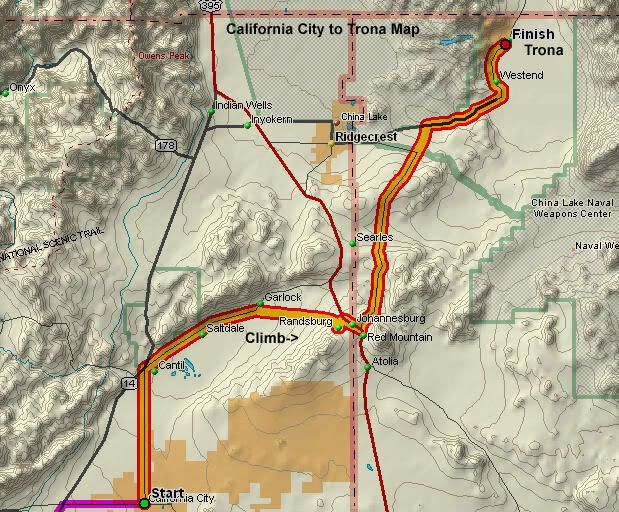

Here is the route:

My chain was sounding a little noisy, so Bill and Rick were busy lubing it. I had a little more to drink, some potatoes to eat, and one of the 20 PBJ sandwiches I had prepared for myself. I love PBJ … especially with apricot-pineapple jelly.

I was in California City about 10 minutes … longer than I wanted. But I got my clothes changed, got some food in me, and I was ready to go.

Back on the bike, and off I went. This next section heads north and slightly downhill on Neuralia Road, skirting the Desert Tortoise Natural area. Just short of Highway 14, we make a right on Red Rock – Randsburg Road and head east. After a series of rollers, we continue east on Randsburg road, and make a long steady climb to Randsburg. This climb can be very hot, and riders often overheat here. The grade is also much steeper than it looks. I had never done this stage, so the climb to Randsburg would be new to me.

By this time of the day, the winds were supposed to be out of the southwest … at our backs. It was not. The winds were from the west, and they were intensifying. Although the road was slightly downhill, the crosswinds cut our speed a bit.

I passed the Honda proving ground. I wonder how many people even know it is there. Railroad tracks. DEEP railroad tracks. Very dangerous.

Literally reaching the end of the road, we made the right turn onto Red Rock-Randsburg Road and headed east. This road has a number of “whoop-de-doos.†Well, I guess it kinda does. If you were going 100 MPH, you might call them that … they’re too long and big to have any fun with. And on a bike, hills like that are a bit of nuisance. Not long enough for you to settle into a long climb, but too long to just power up. I might have just stood up and pedaled hard over them, but remember … that was not in my plan.

But today, with an ever-strengthening westerly wind, those hills were no problem at all. I fairly flew along the flats, and with all the extra momentum, almost made it to the top of each hill without any serious downshifting. This section was going by fast.

I leapfrogged NUBS on this stretch … the guy on the pink fixie and the entertaining support crew. He was doing great.

Soon enough, it was time to turn off and begin the long climb to Randsburg.

I have a fascination for ghost towns, and had been to Randsburg many times before. It’s heyday was in the 1880s, and like almost all towns of its stripe, it had it’s saloons, *****houses and gunfights. What sets Randsburg apart, however, is that it is not really a ghost town. It is still occupied. You can still go into the general store and order up a “phosphate†… a precursor to our modern-day sodas. Look up while you’re drinking it, and you’ll see a tin ceiling, typical of the day.

The Yellow Aster was the largest of the paying gold mines, and it yielded a lot of wealth and kept a lot of miners employed for a good many years. The nearby town of Red Mountain was known for providing Randsburg residents with nightlife and womanly entertainment. Some of the prostitute’s cribs can still be seen along the roadside. Red Mountain was so famous (or perhaps infamous), it would attract paramours from as far as Los Angeles.

With the richest of ore long played out, Randsburg is now the site of a massive “heap-leach†mining complex. “Heap-leach†mining means they dig up dirt with mere traces of gold in it, “heap†it up in massive piles atop plastic sheets akin to those used in artificial ponds, then drip cyanide over the top. The cyanide leaches out the gold, and is collected by drains at the bottom. Gold is then extracted from the cyanide.

This kind of mining results in literally miles of piled up dirt … several hundred feet high. The sheer scope of it would appear to be little different than the hydraulic mining … a practice so obviously favoring greed over common sense that it was outlawed in the 1800’s.

I have no idea why open pit or heap-leach mining is permitted in this day and age.

In any case, the phosphates would have to wait … our route would pass but the outskirts of Randsburg, but none of us would see Randsburg itself. It’s really a bit of a shame.

True to my usual pattern, I caught a couple of riders on this climb. The first looked to be in bad shape. It was hard to fell if he wasn’t feeling well, the heat was getting to him, or he was just tired. I said hello as I passed, but I don’t thing he heard me. Even at a distance, I could hear music playing on his earphones.

The climb steepens a bit as it approaches Randsburg. The climb actually went rather well for me. A couple riders reached the top, and stopped at the intersection where their crew was waiting for them. They too, looked to be suffering a bit.

Not needing to stop, I made the left turn head to US395. On the way, I caught a rider in a blue kit. He didn’t appear to speak English, but somehow got it across to me that he was lost. All I could tell him was to follow me. After arriving at US395, we made a right. I wanted to tell him about then next turn.

“TRONA ROAD!â€

He looked puzzled. I motioned to the left and said it again.

“TRONA ROAD!â€

He appeared to understand.

At this point, I began to think I ascended to Randsburg too quickly and backed off significantly on my speed. My foreign friend kept in sight … making sure he made the turn on Trona Road.

Once we made the turn, we were again heading North. The winds had not significantly shifted and were still out of the West. That meant that the winds would not be of any great benefit to us, but at least, they would not be in our faces.

I had never ridden this section, but it was notable for two small climbs.

Again, I caught people on the climbs and they caught me on the descents. And the crosswinds made the descents entertaining, to say the least. I’d be rolling along at 30-35MPH or so, and get whacked with a gusty crosswind serious enough to move the bike over a couple of feet. Each time this happened, I was able to correct it and stabilize the bike, but it occurred to me that an only marginally stronger gust may be enough to destabilize the bike and make me crash.

I’ve tasted asphalt before. And even at only 24 MPH, it does not taste good. I don’t even want to know what it tastes like at 30-35 MPH, so I slowed down.

And as I did, I got passed.

If not for the crosswinds, the last descent to the road to Trona would have been a real hoot. As it was, it was rather tiring. But soon enough, I arrived at the stop sign. Turning away from the wind yet again, I headed east and started pedaling.

In what seemed to be almost no time at all, I was in my top gear, pedaling fast and going well over 30 MPH on flat ground, and I still felt no wind in my face. How could this be? The only possible explanation was that the winds had strengthened to be over 30MPH, and they were right on my tail, still coming from the West.

Oh God, but this was fun. It was like being on a motorcycle. I pedaled across the desert, into Poison Canyon, and by the “Fish Rocks†in no time at all. I despise most graffiti, but the “Fish Rocks†are an exception. They seem strangely appropriate in a place like Trona.

I think these might have been the strongest tail winds I’ve ever felt.

My crew waited for me ahead. Screw that. I didn’t need any water, and I sure didn’t feel like stopping. I was flying.

I screamed as I flew by.

“MEET ME IN TRONA!â€

They were happy to oblige.

Well, this was a good way to roll into town. I was feeling pretty good. But what’s this? A left curve. Drat. That would mean that I wouldn’t have that wicked tail wind behind me anymore. No matter … I could pedal into Trona with the crosswind.

Then the road turned left again.

I was now headed northwest, and into a quartering headwind. Yikes. That was the end of that party … my speed slowed to a mere 10 MPH. And as I looked up to the road winding it’s way north, I realized that I was still several miles from Trona itself.

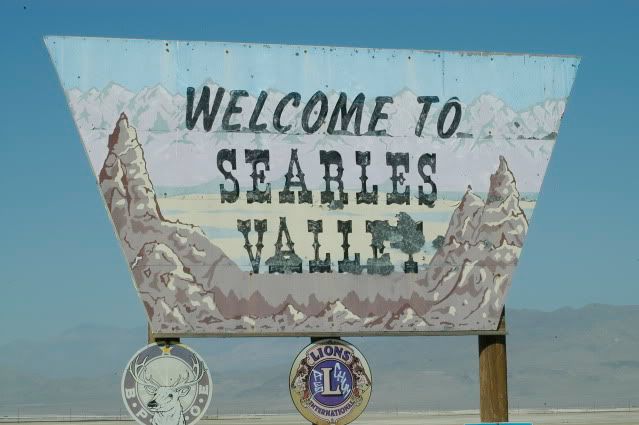

I’ll confess here that I love Trona. I don’t know what it is. It might be the curious mixture of hope and despair. All around are dilapidated and abandoned houses … the product of the company selling those homes to their employees before unexpectedly leaving town and taking their jobs with them. That left a lot of residents holding the bag. But there are also museums, and proud little historical museums on the side of the road.

There is a hopeful little bike path. But it’s condition is so poor, no one uses it.

There is probably no community in California with more churches per capita. But they are closed most of the time. The Catholic Church, a grand, windowless monolith of concrete, has services but once a month, and that is on a Wednesday.

There is the Rite-Valu market:

… but the shelves are mostly empty.

There is a proud little high school, but few students go there. It’s football team, the Trona Tornadoes, practice on a dirt field, reputed to be the only dirt field in the lower 48 states. Grass refuses to grow, and astroturf would be blow away in the desert winds. There are students enough to field a team of only eight players.

As a matter of fact, there is pretty much no vegetation anywhere in Trona. Even crabgrass does not grow here. Instead of lawns, most homes are fronted by garbage and rusted out automobiles.

If the wind is just right, you can smell the chemicals they pump from the depths of Searles Dry Lake. The odor is reminiscent of dirty diapers. Driving through years ago on the way to Death Valley, I actually stopped here to change my daughter’s diaper, only to discover that it was clean, and that the town was the source of the odor.

Perhaps 300 people are employed in the mining operation that dominates the town. But many of them live elsewhere, leaving Trona itself to those on public a$$istance.

Those that know me know that I love Trona. I’m not really sure why. Maybe it’s people like the proprietors of the gas station, who love Trona and would live no where else. They make a mean burrito, too.

My support crew was waiting for me as I rolled into town. At once, they replaced my near-empty water bottle with a full one, shoved food at me, and scolded me for not taking enough endurolytes. But I had been taking enough … probably an average of 3 or 4 tablets an hour, and in truth, it was not that hot. I ate what I could, though I must confess that nothing sounded all that appetizing.

I dunno what it is about cycling in the desert. It is so very easy to lose your appetite, and if you do, it is so very impossible to finish the 508. I know this well enough, and so whether I was hungry or not, I shoved food in my mouth and started to chew.

And there she was. I had heard that Terri might meet me in Trona. Terri had done the 508 with a 4 person mixed team the same year that Saralie and I did it as a mixed double. Too bad I didn’t know her at the time, because we must have been within sight of each other much of the way … we finished within a half an hour of each other. She hadn’t done as much cycling since then as she’d like, and came to cheer myself and the others on.

There is one part of the 508 that is particularly memorable. That comes when you reach the north end of the Panamint Valley and make the right turn to face the most difficult climb of the race … Townes Pass. Most riders arrive there either at or just after dusk. And after making that turn, what do you see?

Before you, a series of flashing red and yellow lights, slowly … imperceptively … crawling up the hill and disappearing into the sky. Like a scene from Dante’s Inferno.

To your right, a king’s view of the Panamint Valley. And a steady line of headlights extending south as far as the eye can see. Like something from the Field of Dreams.

For most of the 508, your only company is your support van and perhaps a rider or two directly in front of or behind you. But at this point in the ride, the sheer scope of the 508 is clear. It is an exquisite community of adventurers. Each pinpoint of light represents someone’s faith in themselves and their crew and teammates. Each is someone willing to lay it on the line.

“I’m going to go to the bottom of Townes Pass tonight.†Terri said.

“That was something I have to see again.â€

While we were chatting, the rider I passed on the Randsburg grade appeared. He stopped just long enough to check in and kept moving. He looked a lot better than he did when he was suffering up the hill. He had recovered substantially.

Terri’s son was there too. A cute, curious kid, holding the remains of a black house key that looked to have been broken off in a lock. He studied it with a discerning, scientific eye.

Terri even brought me a little gift … incredibly sweet of her. Like the fixie support crew, her appearance was like a pleasant mirage.

I would like to have stayed and chatted over a Tronarito with her, but it was time to get back on the bike.

Stage III – Trona to Furnace Creek

Before me was the Trona “bump.†A 1000 foot bump. It was steady, but not steep.

Again, I leapfrogged with some other riders and support crews. This time, Desert Coyote and Vireo, who I now recognized as the guy I passed on the Ridgecrest Grade. Trona is behind me.

I’ve related how among people who are about the same speed, I generally pass in the climbs, get passed in the descents, and hold my own in the flats. That pattern repeated itself in this section. I had passed Vireo and Desert Coyote on the bump.

The top gives a great view of the Panamint Valley … and a great descent.

On the descent, I expected that they’d pass me. I was right … at least about Desert Coyote. I later found out that Vireo had car trouble (flat tire, flat spare) on this stretch.

Buffetting crosswinds were enough to convince me to keep my speed down. Desert Coyote whizzed by me and left me in the dust.

I was dressed in little more than underwear, riding a bike weighing 17 pounds. And the only thing between me and disaster was a chunk or rubber as wide as a dime and as thick as a callus. Under those conditions, a high speed, crosswindy desert descent didn’t make sense to me.

I spent two days in the hospital courtesy of a blown tire at a mere 25 MPH. A little high school physics told me that a crash at 40 MPH would have two and a half times the energy. Facts enough to keep my speed reasonable.

I’ve tasted asphalt. It’s bitter. It’s hard. It’s to be avoided.

In years past, the road through Panamint Valley was full of expansion cracks and potholes … a decidedly unpleasant experience. The road is improved now, but it’s still a long, featureless road that extends out before you to the horizon.

We arrived at Death Valley National Park.

When I got down to the bottom of the Panamint Valley, it became obvious that the winds had intensified and were now coming almost directly out of the south. That would make for a quick ride.

That was the good news. But what would happen when we got to Stovepipe Wells and turned into the wind? I tried to stay in the moment and not think about it.

We arrived at Highway 190 and the bottom of Townes Pass, and it was still daylight.

The sun was casting marvelous shadows on the Panamint Mountains, and the sky was ablaze with orange and red hues. The same storm that was causing all the wind was making for some beautiful clouds, and spectacular lighting on the desert floor. It was just the kind of moment that would ordinarily have me scrambling around with my camera.

Not this time. I scrambled, all right. But I was scrambling around looking for a friendly bush instead. I changed shorts and jerseys once more, and for the first time in my life, donned clear sunglasses … if the weather predictions were correct, I would need them to keep the wind and sand out of my eyes.

The bottom of Townes Pass is about 200 miles into the 508. I checked my watch. It was 6PM.

“Yikes. 11 hours.â€

Rick heard me.

“Yep, you did a double century in 11 hours. Not bad.â€

Yea, not bad, but not as good as I was hoping. I expected to make it there in great time, with all the predicted tailwinds. Trouble was, the winds were there, but much of the time, they were crosswinds, not tail winds. That allowed me to get to the Townes climb in good time, but not great time. And now, the winds were coming directly out of the South. I could hear the wind whistling in the creosote.

The prediction was that the winds would be from the SW most of the ride up. After sunset, the winds were to slowly decrease until about 4AM, then slowly increase again at about 11AM Sunday morning … again, from the southwest. I didn’t relish the notion of riding into a headwind all the way to Twentynine Palms. I didn’t dare share my plan with Saralie or Rick, but I had to tell someone.

“Listen, Bill. The winds are supposed to calm down early Sunday morning. If they do, I’m not going to want to stop at Ashford Mills to sleep. I want to make hay while the sun shines and get as far as possible before the winds start up again. Shoshone. Maybe even Baker.â€

He nodded. We both knew that it depended on what the winds actually did, not what they were predicted to do. Winds are notoriously fickle.

A van passed with 3 bikes on the roof.

“The teams. They’re passing us.â€

Teams start the ride 2 hours after the solos. Team riders have the luxury of going all out on each stage, and they pass all but the fastest riders. That they were passing us now meant that they were doing 200 miles in about 9 hours. That’s moving.

I had some more to eat, changed shorts and jerseys, watered up and hopped back on the bike. Before me was Townes Pass.

Townes Pass is the “queen†of the 508. It’s a long climb … over 3500 feet in a little under 10 miles. And parts of it are quite steep … about 13%. My thoughts preoccupied with the winds I expected in Death Valley, the climb up Townes Pass did not concern me.

I started the climb.

Behind me were the lights that Terri traveled a hundred miles to see.

I got a little preview of those winds on the way up. The lower portion of Townes Pass … the steepest portion … has southern exposure to the Panamint Valley. Riding along with only a guardrail to shelter me from those winds, I got buffeted about. Sometimes, the wind was in my face, and that made for a difficult climb.

The sky darkened, turning to black as I ascended. A support car surprised me with a flash.

The Townes climb flattens out as it approaches the top. Recognizing that I was nearing the top, I motioned the van to pull over in a pullout.

“What’s wrong?â€

“I’m fine, but I need my light.â€

Well, my second light. The rules required that I have a headlight since 6PM, and to comply with those rules, I put a small helmet light on back at the bottom of the Townes Grade. But having done the Townes descent in the dark before, I knew I needed something more.

The Townes decent is steep, and relatively straight. But it has rises and valleys in it … and those valleys are unreachable by your support vehicle’s headlights for brief, but terrifying instants of time.

So here is what happens. You are whipping down the highway at 40 MPH, hands tightly gripping the handlebar, eyes scanning ahead to identify the stray coyote, jackrabbit, rock, or tumbleweed that might be in the way. And suddenly, your support van dips into the road, and like a curtain, darkness descends on the road in front of you for several seconds. During that time, you can see nothing. No rocks, no animals, no bumps, and no curves. Nothing.

Several seconds sounds like nothing too … but it feels like eternity when you’re riding blind at 40 MPH. Don’t believe it? The next time you’re driving on a dark night, turn off your lights and see how comfortable you are leaving them off for any length of time.

Other riders apparently have no problem with this, but the notion of my support vehicle’s headlights illuminating a Death Valley denizen only moments before I hit it is enough for me to want some serious illumination on this part of the race. It’s more than worth stopping for a few minutes.

I grabbed the light, affixed it to the handlebar, and we were off.

When I summitted Townes Pass in 2006, there were a gaggle of vehicles at the top … no doubt because they included both solos and most of the team riders. This year, I must have been either ahead or behind the pace, because this time, there was no one at the top at all to greet me. Kinda lonely.

I approached the top.

I felt a push.

It was the wind. Getting blown over a pass is a rare sensation … and a sure sign that the winds were again intensifying.

The top of Townes Pass is another place where being a 508 veteran has its advantages. Since Townes Pass is at about 5000 feet, most riders are a little chilled at the summit, and stop to don some clothes for the ride down.

I knew better. All one has to do is descend for perhaps 5 minutes, and the desert air warms dramatically. There is no point in jacketing up at the top of Townes Pass.

I turned my headlight on and started my descent into Death Valley … and down to face the winds I had been fearing all week.

What a descent. I had the wind at my back, a steep descent, and a strong headlight to light my way. I suppose I could have hit 60 MPH or more on that descent. But what I didn’t have was nerve. It seemed like I was going 100 MPH, but later, my odometer would reveal that I went no more than 40 MPH anywhere on the 508, and that would include this descent.

By the time I arrived at Stovepipe Wells, my pace slowed to a maintainable 20 MPH. It was dark. Everything was closed.

And the winds were calm!

Was it possible that I would avoid a windy nightmare through Death Valley? All that worry for nothing?

No, the Panamints were shielding me from the worst of the winds. And in fact, I was still heading northwest. What I was getting was a tail wind.

That would end shortly after I left town, and I turned east.

“Sand Dunesâ€

The Sand Dunes are lovely, soaring dunes, perhaps 500 feet high, and a short distance from highway 190.

If I ever wondered why the dunes were in this particular geographic location, that question was answered that evening. As calm as the winds were at Stovepipe Wells, they were anything but calm that a mere 5 miles out of town.

Riding out there in the night, I wouldn’t have said that the cross winds were all that horrible. Yea, they were strong. Yea, they impeded my progress. Yea, they meant I would pedal through sheets of blowing sand, dodging little sand dunes forming on the road itself. But I could see, and it was still rideable. If this was all I had to deal with, I would be all right.

But this was a mere prelude, and I knew it. The true test would come after the turnoff to Scotty’s Castle. That was where the course turned in a southerly direction, and I would begin heading into the wind rather than across it. It looked like it might be nasty.

I pushed through the sandstorm, squinting to keep the sand out of my eyes.

Just before the Scotty’s Castle cutoff is a small hill. And here it was.

I climbed it with little regard for the hill itself … my concern was the wind on the other side. This is where I expected the winds to blow in earnest.

And blow they did.

Although I was now going downhill, I had to push considerably harder on the pedals than I did moments ago while going uphill. The wind buffeted me from the side, and sand blew in my eyes.

I pushed harder.

“Furnace Creek 17â€

Holy crap. 17 miles of this! My commute to work is about 17 miles, and I can do that easily in about an hour, but at my speed, it would be closer to 2-3 hours. Two to three hours of hard pedaling into a vicious, unrelenting wind. Exposed.

This is ugly, but doable. I pushed along, making what pace I could into the strengthening winds.

“Beatty.â€

Here was the second cutoff. Soon, we would turn even more southward … and even more into the wind. I pedaled harder. The wind pushed back, howling into my ears to the point where I could hear nothing else.

What’s that?

A scorpion!

I presumed, of course, that Death Valley must be home to many scorpions, but I had never seen them on the road. This evening, I would encounter a half dozen at least, sitting motionless on the asphalt, confused, and gripping the asphalt against the wind. I pointed them out to my crew, but they apparently couldn’t see them.

A pair of eyes appeared, crossing the road on the horizon. A coyote. He stared at my approach, his head following me as I approached. His expression was that of curiosity … as if to say … “What are you doing here?â€

I dunno why I howled at him … it seemed like the thing to do. And when I did, he turned and ran away.

I’ve ridden between Stovepipe Wells and Furnace Creek before. It’s a pleasant, ethereal experience. The roads, at least from Stovepipe Wells to Furnace Creek, are smooth, and the ride goes by quickly.

Not tonight.

It was dark, and I have no idea how fast I was going. I did know that I was in a ridiculously low gear for riding on flat pavement. My guess is that I was going perhaps 7 or 8 MPH, and struggling mightily to do it. The winds were taking their toll.

I could see a few red lights in front of me along the darkened ridge. Team riders, who had passed me going a phenomenal … uh … 9MPH. I crawled … literally crawled along. My eye on the ridge. Pushing … hard.

I crest another ridge, hoping to see the lights of Furnace Creek.

Nothing … not even the little red lights had had been following. They had disappeared on the horizon.

More company … another scorpion.

We turn even more into the wind. I pedal still harder, and hold the handlebars harder. It doesn’t seem possible, but the winds are still intensifying. And gusting.

I know from other rides that Furnace Creek does not announce itself from a distance. You really can’t see anything until you’re right upon it.

After what seemed to be a windy eternity, a sign appears:

“Cow Creek.â€

Is that sign wiggling in the wind? Or am I just exhausted?

Like a salmon struggling up a river of wind, I pedal on.

“Harmony Borax Worksâ€

Still closer, I think. I have no idea what time it is. It doesn’t really matter. My mind is focused on getting to Furnace Creek. And that is taking forever. The wind resistance wore me down physically. The howling in my ears wore me down mentally. I was thankful I couldn’t see my speedometer. Some things, like how slow I was going, are better left unknown. Just keep pedaling.

Finally, Furnace Creek appears. As I approached, the trees and structures helped to break the wind.

I wouldn’t say I was vanquished when we rolled into the Chevron Station at Furnace Creek. I wasn’t spent. But I was spending faster than I wanted, and getting precious little mileage for all that effort. If I had stopped to think about it, I would have told myself that those were the strongest headwinds I had ever pedaled into.

I knew it was better not to think … just pedal.

I dunno what my crew did here. They might have gassed up. They might not have. I don’t remember. I do remember sitting down on a bench to take a short rest. Not because I wanted to, but because I needed to. And I remember eating something and drinking something. My crew insisted, shoving food in my mouth, and admonishing me to eat and drink.

I dunno how long I sat there. Perhaps it was 10-15 minutes. Longer than I wanted to. But I had to rest and take a break out of that wind.

I dunno if it was the food, the drink, the encouragement … or if it was because the wind was calmer in Furnace Creek. Maybe it was a summer of training, riding long distances again and again. But after a short rest, I had completely recovered and was ready to do battle with the winds again.

Bill took another picture of me. I have no idea why I look so chipper here.

I expected bad winds pedaling to Furnace Creek. They were worse than expected.

I steeled myself for the challenge. I knew all along that the winds would be bad in Death Valley. My plan was to keep pedaling, no matter how low the gear, no matter how slow the speed. And when those winds finally died down at 4AM, make as much distance as I can.

Stage IV – Furnace Creek to Shoshone

The reader will recall that mere hours before, I had dreams of making it to Shoshone … perhaps even Baker before stopping for some sleep. The winds approaching Furnace Creek put a stop to that folly. I would be lucky to get to Ashford Mills in one piece.

I pushed off. It was a little after 11PM.

As I expected, as soon as I left the shelter of the structures and trees of Furnace Creek, the winds returned. I got low on the handlebars and pushed.

Not that I would have noticed in all the wind, but the road to the Badwater cutoff is slightly uphill. Just south of the turnoff, the road heads downhill. Enough of a downhill so that without wind, you easily toot along at 25 MPH or so. What was it like on that moonlit night? After making that right turn, I had to downshift to keep going. Just for yuks, I stopped pedaling and immediately came to a halt.

I was now heading directly into the wind again, and incredibly, the wind had … again … intensified.

Headwinds are every cyclists worst enemy, and in my 20+ years of serious cycling, I have had my share of windy sufferfests. But none of them … none … could prepare me for the next several hours pedaling into that gusty desert gale to Badwater and beyond.

How strong were they? I was sorely tempted to stand up and pedal. I even tried it once. That experiment proved futile … a gust of wind struck me so hard, it lifted my front wheel right up off the asphalt and moved it over 6 inches. So much for that.

“I saw that.†Bill would say later. “That was intense.â€

Not only was the wind strong, but it was gusty. And those gusts would come from either direction, plus or minus thirty degrees or so. It made it virtually impossible to keep the bicycle going straight. I weaved all over the road like a drunken sailor. It may have been 17 miles to Badwater, but with all the weaving around, I’m sure I pedaled a longer distance than that.

My front wheel was now an airfoil. I tried to keep the wheel pointed straight into the wind, but the wheel would be blown off center with every gust. And once it got blown off center, it would catch the wind even more. It took muscle to bring the bike around and back into the wind. Worse yet, there was no point in steeling myself for the gusts … they came in random directions. I would just have to correct them as best as I could when they came.

Thinking about it now, I realize that part of the problem was also the pitiful speed I was making. At slower speeds, the gyroscopic stability of the wheel was almost nil. And believe me … I was going slow. It was like being on a trapeze … a very windy, dark trapeze.

I stopped. My support crew pulled along side of me.

“WHAT’S WRONG?†Bill yelled to be heard over the hurricane.

Kind of an absurd question … EVERYTHING was wrong at this point. But since we were all endurance cyclists, the context was clear … why are you stopping?

“NOTHING!â€

Yes, I lied. But I did have reason for stopping.

“I NEED TO TAKE A DRINK, AND I DON’T DARE TAKE MY HANDS OFF THE HANDLEBARS!â€

I grabbed a bottle and drank. The residue splashed my chest. Another gust came, and nearly blew me over. Bicycle cleats are hard and offer no traction whatever.

Between gusts, Bill snapped a picture.

I wear a small crucifix. You’ll note it is blown all the way to the side. It would occasionally slap my ear. Note that the wind is blowing my helmet to one side, my jersey open, and flat against my chest. And you can get an inkling that I am leaning forward so I’m not blown backwards. Why am I smiling? I have no effing idea.

My drink taken, I cleated in, pushed off, and began the sufferfest anew.

The wind continued to buffet me around like a child going the wrong way in a subway, randomly knocking me back and forth. I tried as best I could to keep my bike in my lane, and failed often.

At this point, us 508ers were the only ones on the road. That was a good thing, as I got blown across the road into what would have been oncoming traffic countless times. Bill later told me that he worried about what he would do if someone approached us from the rear. They might hit me as I got blown over to the left of the van.

“Oh *****!â€

This time, I was blown all the way over near the shoulder on the other side of the road. I muscled the handlebar over back to the center of the southbound lane. I didn’t dare attempt riding near the shoulder.

Instead of heading directly south, the road follows the general outline of the alluvial fans that extend from the Funeral Mountains. The most intense winds were to be had when we rounded a curve where the road poked into Death Valley itself, creating a venturi effect.

I looked at road marker.

“6.â€

I’ve gone only six miles since the turn off!? Gawd, don’t tell me that! I have another 11 miles to go?!

At this point, I was pedaling hard in my lowest gear … a gear usually only use to climb steep grades. I had no idea what my speed was, but it was abyssmal … perhaps 4-5 MPH. On top of that, because I was getting blown all over the road, my actual speed in the direction I wanted to go was probably lower. This was going to take a long time, and it would feel even longer than that.

I stopped for another drink. The van pulled beside me. My statement was in the form of a command, not a suggestion.

“WE ARE STOPPING IN BADWATER. I NEED TO REST THERE.â€

They didn’t argue. I was in no mood to negotiate.

In training for the 508, I learned to never count the miles until a rest stop or until the end of the ride. Just turn the pedals until you get there. Otherwise, you enter the “watched pot never boils†syndrome. But I violated that rule here … I couldn’t help it.

Another road marker.

“8.â€

A recumbent cyclist passed me, screaming:

“THIS IS INSANE!â€

More screaming wind. More near miss encounters with the shoulder. More pushing.

“11.â€

The sky was clear and the moon was full. A lone lenticular cloud could be seen over the Panamint Mountains. You don’t often see lenticular clouds at night. But then again, you don’t often get winds like this, either.

The sandy sheets of wind at Stovepipe Wells now seemed like an innocen memory. I found myself wishing that there as a little debris in the wind … at least, perhaps I could see the gusts coming and brace myself. But whatever debris there was to be blown was long gone, and the 60 MPH gusts would strike me with no warning whatsoever.

I have no idea how long I battled out there. It’s all a blur of wind. It seemed an eternity between mile markers. Some weren’t there at all, leaving me to wonder whether they were missing or whether I had slowed even more than I thought.

But finally. Mercifully. Badwater came.

Lucky for us, the alluvial fans north and south of Badwater form a little cove … shelter from the wind. I could stand up without getting blown over, and my crew and I could be heard if we screamed loud enough.

Saralie had gone to use the restroom. She returned, announcing that it was “truly disgusting.” Knowing full well that males are less picky about such things, I walked confidently over to the restrooms to do my business.

Saralie was right. This was “disgusting” in the highest (or lowest) sense of the word. The smell was awful. I had a light on my helmet, but I didn’t dare look into the abyss. Some things are better left unknown.

Or so, I thought.

Ignorance is not always bliss. As it turns out, the smell was only the beginning.

KERPLUNK!

Backsplash, and lots of it. It soaked every part of my arse that wasn’t shielded from the seat. Distressing when using *any* toilet, but especially so when using a glorified hole in the ground.

OMGing as that was, it paled to the nightmarish ride I had endured just to get to Badwater. My consciousness still clouded by the single-minded determination to keep going, I just wiped my arse off the best I could and exited. I don’t remember if I even told my crew about my little baptism at 242 feet below sea level.

And no, I didn’t pause to look into the abyss before I left. Some things are truly best left alone.

*Sigh* … just one more adventure, I guess. This was grim. I was not looking forward to getting back on that bike.

Once I did, I began to notice another curious thing. Support vehicles, passing me, then disappearing on the horizon. Since the rules require them to follow their rider after dark, there was only one explanation … they were giving up. It had been happening for a while now. But I was so focused on staying on the road and keeping moving, I failed to give it much thought.

I wondered aloud if that would be my fate.

I passed a support vehicle on the shoulder. They had given up and were packing it in. I have no idea how they proposed to get their bikes on the roof of their car in that tempest. I would not have attempted it.

The support crew looked at me as I approached, stood there and applauded, shaking their heads. It was a much appreciated demonstration of respect.

It seemed impossible, but the winds continued to intensify. I wondered whether I could possibly reach Ashford Mills.

In retrospect, there was another factor. I didn’t get a lot of sleep after 1:30 AM the night before, and I was starting to feel it. The howling wind. The ground slowly, rolling by. At times, it felt like I was watching this whole spectacle from a distance. Like someone else was doing it. About the only thing keeping me awake was the terrifying crosswinds. I had to pay attention.

“OH ****!â€

A gust of wind, the strongest and longest lasting yet, struck me on my port side. I had been pedaling on the center line, hoping to be somewhere in the middle so I had plenty of room to steer out the gusts. This gust caught my wheel and pushed me in front of my support crew, clear across the road and onto the shoulder. My front tire skidded in the sand and rocks and gave out.

I was down.

That’s a first for me. I’ve never been blown off the road. Never. Not even close.

My support crew pulled over, and Rick immediately got out and helped me up. I looked down and saw that my left leg had taken the brunt of the fall. It was bloody and scraped up pretty good, with a nice red bleeding cherry more than an inch in diameter on my knee.

On my right, I noticed a sign.

“Mormon Pointâ€

Rick and I picked up the bike, and stood there to the right of the van … leeward of the direction of the gusts. All the same, the wind slapped us and made it difficult to stand. My bike was between us, and we both had our hands on it. With each gust, the rear end of the bike would flap like a beach towel in the wind.

All this time, the crew could only guess how severe the winds were. They were somewhat calmer in the shelter of Badwater cove where they exited the van. Not so at Mormon Point … the place where the Funeral Mountains poke deepest into Death Valley. This was a venturi … and the winds would be the strongest.

“HOW FAR TO ASHFORD MILLS!?†I asked, again screaming to be heard.

“ABOUT 8 MILES!â€

Eight miles is a very short distance on a bike. But tonight? In these winds? It was an hour and a half or two hours away! Screw that.

“THERE’S NOTHING THERE THAT ISN’T HERE. LET’S SLEEP HERE.â€

Rick paused. One thing about endurance cycling is that you have to keep going until you can’t. I guess it appeared to him like I could keep going. Maybe I lost my nerve, I dunno. All I knew is that continuing to ride in those winds would have been absurd to the point of being dangerous. Enough was enough. Rick agreed.

Rick and Saralie scrambled to ready the van for my sleep stop. Saralie had endured hurricane force winds in the 2008 Death Valley Double, so she is quite familiar with riding in the desert in terrible winds. Now walking around outside to prepare the van, she fully appreciated just how strong the winds were.

“I think this is even worse. I couldn’t ride in this.â€

Not surprising … I outweigh her by at least 50 pounds, and neither could I. It was time to stop, and the more I thought about it, the better my decision to stop sounded.

Finally, we laid the bike down in the rocks, hopped in the van and slammed the door shut. The gusts rocked the van back and forth.

I was so busy, grimly focusing on keeping the bike upright and going forward, I didn’t have time to really think about what I was actually doing. That burden removed, the absurdity of trying to ride a bike into a near hurricane was obvious … even to me. I began to laugh hysterically.

I wasn’t sure whether the crew thought I lost it or what. Saralie later confessed that she was surprised at how good my spirits were through this ordeal. Good spirits, hell. I had no choice but to laugh. How could I do anything else?

For the first time since the bottom of Townes Pass, I checked the time: 5:30! I had been riding for 6 1/2 hours and gone perhaps 32 miles!

Oh no! Not only was I exhausted and in the middle of a hurricane … I was way behind schedule. By this time, I had hoped I’d already have slept and been well on my way up the Salsbury Grade.

I became aware of a dawning reality. Until now, I had not seriously considered the possibility that I would DNF. Yea, objectively there is always that possibility … there is on any ride. But this was different. I began to see that DNFing was more than just a possibility … it was a certainty if the winds did not subside. And there was no reason to believe they would. They should instensify as the sun rose … and that would happen perhaps an hour from now. I was screwed.

At this point, I had resigned myself to my fate. There was no way I could pedal another 200 miles or so into this wind. No way in the world.

The 508’s last time station is at a lonely crossroads called “Almost Amboy.†In 2007, some creative souls working that time station took it upon themselves to create “Amboy Memorial Gardens and Lemonade Stand†… a mock graveyard, with little headstones for riders who had failed to finish the 508 within the allotted 48 hours.

“DNF. OSTRICH. 2004â€

“2002 RED ROOSTER. DNFâ€

“JACKRABBIT. 1994 DNFâ€

I wanted like anything NOT to have my totem on one of those little tombstones. But I could see that tombstone clearly now.

“SKINK 2009. DNF.â€

Egad … another spring and summer training to do this all over again.

I comforted myself with the fact that if there was ever a 508 where DNFing was to be excusable, this was it. It makes no sense to continue when you can’t keep your bike on the road. I didn’t like it, but I could make peace with it. At least, I would have plenty of company in DNFland.

Since we were in DNFing anyway, there was no point in setting an alarm. I laid down and instantly fell asleep …

My eyes opened. Everyone in the van was quietly asleep. Bill in the driver’s seat, Rick in front, and Saralie next to me in the passenger seat.

We were at Mormon Point. It had been only an hour and a half since I got blown off the road. But the sky was blue and the shadow of the Funeral Mountains was retreating down the Panamints. The Death Valley floor would soon be in daylight. The world looked different. Different as … well, different as night and day.

I was wide awake. My leg was still a little sore from my encounter with the shoulder, but other than that, I actually felt refreshed.

I could hear that it was still windy outside, but the van did not appear to be buffeting nearly as much as last night.

I didn’t want to wake the crew. It had been a long night for them too, and they needed rest. But after a few minutes, Bill stirred in the driver’s seat. Not wanting to wake Rick or Saralie, I whispered.

“Well, Bill … what do you think?â€

The context was clear. Should I keep going?

“I dunno man.â€

Despite our whispers, Saralie and Rick soon awoke. At once, we discussed what we should do. We all knew that if the winds had not subsided, we might as well pack it in. Rick had just attempted the 2009 HooDoo, and he encountered winds that forced him to DNF. It happens.

The world looks different in daylight … so much more hopeful.

Saralie had a proposal. I listened.

“Well, it’s daylight. We don’t need to follow you anymore. Why not just start riding, and we’ll head up to Shoshone to check out the winds. If the winds are like they were last night, we can quit. If they’ve calmed down, we can keep going.â€

That made perfect sense to me.

At once, I prepared to do battle with the winds again. But I was refreshed and ready to go. The bike was sitting outside like a dead animal. Overnight, the winds had flipped the front wheel over even though it was laying flat on the ground. I half expected it to have been blown back to Badwater.

I opened the door. I dunno how this was possible, but it was at once cooler and less windy than only two hours before. Oh, it was still windy. But not nearly AS windy. This was doable.

“On second thought, why don’t we follow you to Ashford Mills first. We’ll head off to Shoshone when you start the climb.â€

That sounded even better. So I mounted up the bike, clipped in, and started riding.

I had done a training ride where I rode 300 miles, slept a few hours, then got back on the bike to ride another 100. And let me tell you, getting back on the bike is not a pleasant experience. Your legs are stiff. Your arse is sore. You’re tired.

But inexplicably, that was not the case here. I was not stiff. I was not sore. I wasn’t tired. The drying scabs on my scraped up leg were noteworthy, but little else.

I have no explanation for this. Maybe I just seemed refreshed, because ANYTHING would be an improvement from my condition the dark night before. But for whatever reason, I was actually eager to get on the bike and start riding. And when I did, I felt great.

I guess all that training was good for something.

Another dawning reality. The wind had died down considerably! Yes, it was still windy … as I approached Ashford Mills, I was peppered with more sheets of blowing sand, much like I was in Stovepipe Wells the night before.

But just like Stovepipe Wells, it was doable. Sandy, but doable. And the wind was more from the East than the South … a crosswind. I got to Ashford Mills feeling refreshed, and had no desire to stop whatever. I kept going and made the left turn to begin my ascent of Salsbury Pass.

I stopped briefly to speak to the crew.

“Follow me up the grade until I get to Shoshone. I don’t care about the winds … I want to make it that far.â€

True enough. I had struggled up Townes Pass in crosswinds, braved the sheeting sandstorms of Stovepipe Wells, fought the whipping headwinds all the way to Furnace Creek. Since there was a timesttop there, there was a record that I made it that far.

But now, I had battled my way to Mormon Point, one foot at a time. I had my wheel picked up by the wind. I got blown all over the road, and finally … off the road. If I quit before I got to Shoshone, the official records would show that I made it to Furnace Creek, and that is all. If I made it to Shoshone, at least I would get some modicum of credit for the sufferfest I endured that night.